Americans view the sweeping changes in family arrangements that have occurred over the past half century with a mixture of acceptance and unease.

Not surprisingly, the people who are living in new arrangements—cohabiting couples or single parents, for example—are the most accepting of them. So are younger adults, who have grown up amid a world where single parents, same-sex couples and working mothers are more of a fact of life than they were for older generations.

Among the groups most uneasy about the changes are married adults and older adults, especially men. There are some regional variances as well: Americans who live in the Midwest and South are more disapproving than those in the East and West. And as might be expected, attitudes about the new types of living arrangements generally track religiosity, ideology and political party affiliation, with the more conservative camps within all of these groups most likely to be troubled by the changes.

The Pew Research Center survey asked a general question about the growing variety of new living arrangements, and also tested responses to seven specific social trends that bear on family life today.

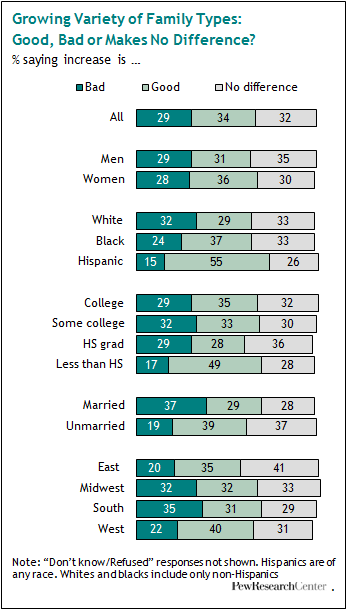

On the overall survey question about the growing variety of family living arrangements, there is no dominant answer among respondents. As shown later in this chapter, approximately equal shares of American adults say the growing variety is a good thing, bad thing or makes no difference.

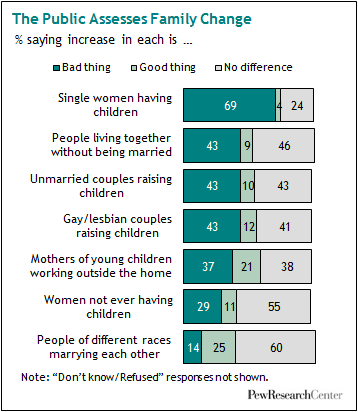

Asked about the seven trends, most Americans disapprove of women having children without a man to help raise them. More than four-in-ten are critical of the rising numbers of unmarried couples raising children, of gay and lesbian couples raising children and of people living together without getting married—representing a lower level of concern but still a substantial minority. There is less disapproval of three other increasing trends—mothers of young children working outside the home, childless women and racial intermarriage.

Single Mothers and Others

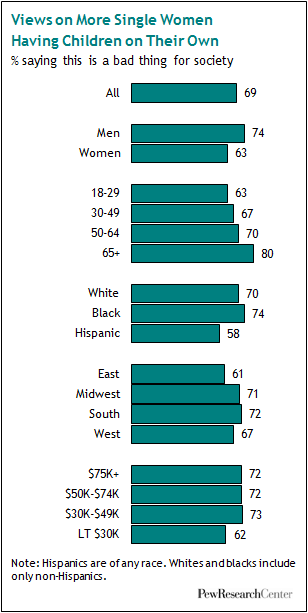

Among the seven trends tested that affect living arrangements and family life, respondents have the highest level of disapproval (69%) for the growing number of single women who have children without a male partner to help raise them. Only 4% say it’s a good thing, and 24% say it doesn’t make much difference for society. A majority of men and women, all age groups, and all major race and ethnic groups disapprove of unmarried motherhood. Men, older adults and whites or blacks are particularly likely to disapprove.

Men (74%) are more likely than women (63%) to say that the trend toward single mothers without male partners is bad for society. Whites (70%) and blacks (74%) are more likely than Hispanics (58%) to say so. Americans ages 65 and older (80%) are far more likely than younger age groups (63% of those ages 18 to 29; 67% of those ages 30 to 49; and 70% of those ages 50 to 64) to be critical of these single mothers. Within different age groups, men are more critical than women. For example, 70% of men ages 18 to 49 say the growing number of single women having children without a male partner to help raise them is bad for society, compared with 60% of comparably aged women, and 81% of men ages 50 and older say so, compared with 67% of women in that age group. Among white men, 76% are critical, compared with 65% of white women.

There is some variance by annual income on the question of rising numbers of women having children without a male partner to help raise them. Here, people with annual incomes of $75,000 or higher (72%) are more likely to be critical than are people with annual incomes of less than $30,000. People living in the Midwest and South are more critical of the rise in single mothers than are those living in the East.

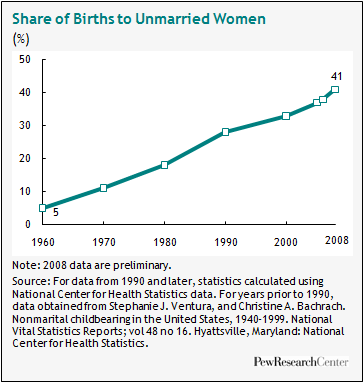

According to National Center for Health Statistics data analyzed in a recent27, the share of births to unmarried women rose to 41% in 2008 from 5% in 1960 and 28% in 1990. The share of births to women who are unmarried varies widely by race and ethnicity. More than seven-in-ten births to black women are to unmarried mothers, compared with about half of births to Hispanic women and about three-in-ten to white women. However, the share of births to unmarried women has risen most rapidly for whites since 1990.

There also is wide variation by education level among unmarried women who give birth. Most births to college graduates are to married women. Most births to women with less than a high school education are to unmarried women.

Unmarried Couples

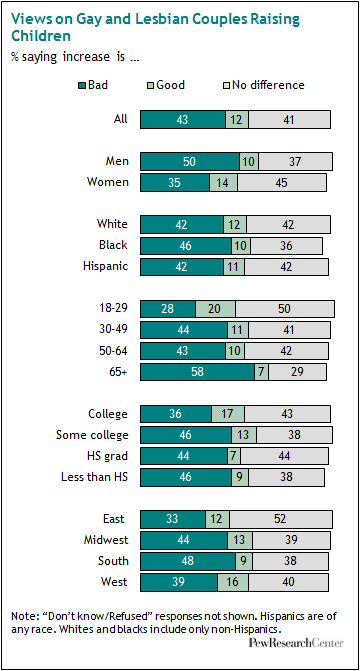

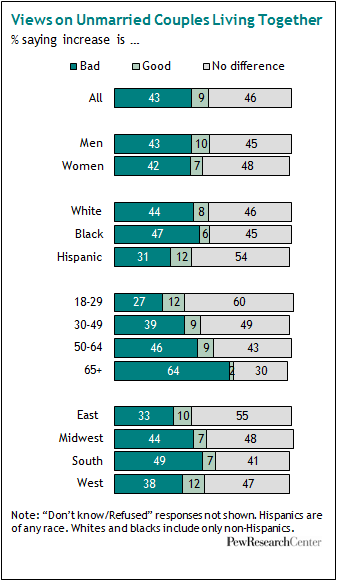

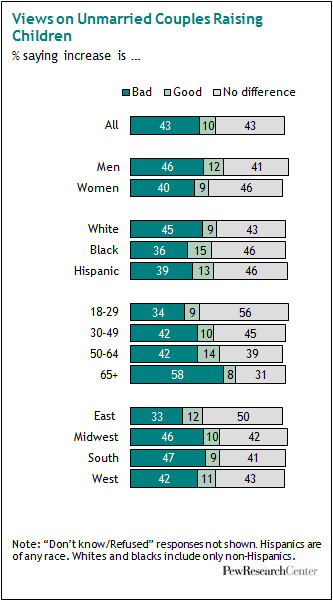

Americans overall are equally likely to disapprove of gay and lesbian couples raising children, unmarried couples raising children and unmarried people living together—43% say each of these growing trends is bad for society. There are no notable differences between these trends in the share of adults who say that it is good for society or doesn’t make much difference that more gay and lesbian couples are raising children (12% say it’s good; 41% say it doesn’t make much difference), more unmarried couples are raising children (10% good; 43% little difference) or more unmarried people are living together (9% good; 46% little difference). However, there is wide variation on these questions by age group and—on the question of same-sex couples with children—by gender.

Most adults ages 65 and older are critical of these unmarried couples, whether they are same-sex or opposite-sex couples. Most young adults, ages 18 to 29, are not. Asked about same-sex couples raising children, only 28% of the youngest adults say this rising trend is bad for society, compared with 58% of the oldest adults who say it is. Adults ages 30 to 49 and ages 50 to 64 fall in between, at 44% and 43% critical, respectively.

There also are large gaps in disapproval ratings between the youngest adults (34%) and oldest adults (58%) over unmarried couples raising children. They also disagree about unmarried people living together—only 27% of the youngest adults say this growing trend is bad for society, compared with 64% of the oldest adults who feel that way.

Gender is strongly linked to differing attitudes on same-sex couples raising children, but less so to attitudes about unmarried couples raising children or unmarried couples living together. Men (50%) are markedly more likely than women (35%) to say the rise in gay and lesbian couples raising children is bad for society. This is true even at young ages: 33% of men ages 18 to 29 are critical, compared with 23% of women in that age group.

The gender gap is even wider among adults ages 50 and older: 60% of men in that age group say same-sex couples bringing up children is bad for society, compared with 39% of similarly aged women who say so.

There are no significant differences among Americans of different education levels in views on unmarried couples raising children and on unmarried couples living together overall.

But on the question of same-sex couples raising children, college graduates are least likely to be critical. Among those with a college degree, 36% say this growing trend is bad for society, compared with more than four-in-ten Americans with some college education (46%), adults with a high school diploma but no college (44%) or those without a high school diploma (46%).

By region, people living in the Midwest and South are more critical than those living in the East of all three types of unmarried couples tested—gay and lesbian couples raising children, unmarried couples raising children and unmarried couples living together.

Public attitudes on same-sex couples have softened in recent years. In a 2007 Pew Research Center survey, 50% of adults said that gay and lesbian couples raising children was bad for society, compared with 43% in the 2010 survey. A growing share—34% in 2007 and 41% in 2010—say this rising trend doesn’t make much difference.

Along these lines, a recent analysis by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press found that for the first time in 15 years of polling, less than half of adults oppose same-sex marriage. In two polls conducted earlier this year, 42% favored allowing gays and lesbians to marry, compared with 48% who were opposed. As recently as 2009, 37% were in favor while 54% were opposed. Age is strongly linked to attitudes about gay marriage. Older adults are less likely than younger ones to favor gay marriage.

Using a generational framework, more than half of the Millennial generation—adults younger than 30—favor allowing same-sex marriage (53%), compared with 29% of adults ages 65 and older, the so-called Silent Generation. Among adults ages 30 to 45 (Generation X), the analysis found that 48% favor allowing same-sex marriage. Among Baby Boomers, ages 46 to 64, 38% favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry.

As for male-female cohabitation, other survey data offer evidence of rising approval over recent decades. In 1981, an ABC News/Washington Post poll asked whether people approved or disapproved “of men and women living together without being married if they want to, or is that something you haven’t formed an opinion on?” At that time, 45% disapproved and 40% approved. The share of adults who approve has risen steadily. In 2007, in response to a similar question in a Gallup/USA Today poll, 55% approved of live-in couples while 27% disapproved.

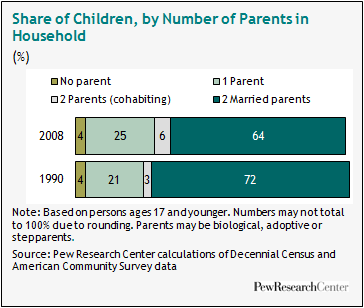

Cohabitation has grown sharply in the U.S. in recent decades. Since 1990, when the Census Bureau first allowed people to designate themselves on the census form as “unmarried partners,” the number of cohabiting adults has nearly doubled. In 2008, 6.2 million households were headed by people in cohabiting relationships, according to the American Community Survey. They included 565,000 same-sex couples.

In 2008, 5% of households (one-in-twenty) were headed by a cohabiting couple, up from 3% in 1990. During that same time period, the share of married-couple households fell to 51% in 2008 from 57% in 1990.

The number of cohabiting households has grown more sharply for Hispanics than for whites and blacks. (The Hispanic population overall is growing more rapidly.) In 2008, cohabiting couples accounted for 8% of Hispanic households, and 5% each of white and black households.

Census Bureau data indicate that 6% of the nation’s children younger than 18 lived with cohabiting parents in 2008. That share rose from 3% in 1990. About 4.3 million children lived with opposite-sex cohabiting parents in 2008, and about 204,000 children lived with parents in same-sex cohabiting couples in 2008.

According to other researchers, most of the increase in the percentage of children being born to unmarried women since 1990 is due to births to women who are living with an unmarried partner.28 A recent Census Bureau report, using data from the Current Population Survey, estimated that of 4 million women who gave birth in 2008, 425,000 were living with an unmarried partner.29

Working Mothers

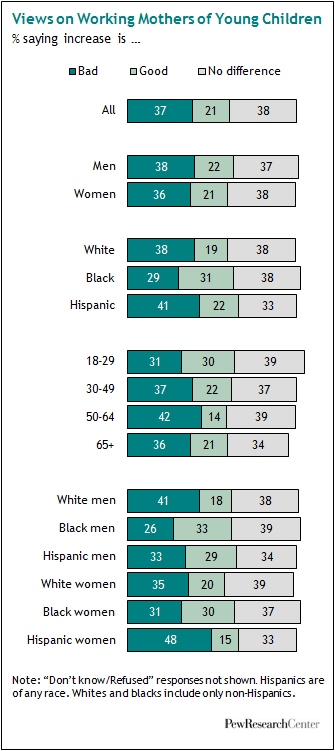

On the rising trend for mothers of young children working outside the home, 37% of adults disapprove, 21% approve and 38% say it makes little difference. There are fewer strong differences across groups than on questions about unmarried and same-sex couples raising children.

Attitudes are similar for men and women, and among age groups. Men ages 50 and older (45%), however, are somewhat more critical than women in this age group (35%).

By race and ethnicity, whites (38%) and Hispanics (41%) are more critical than blacks (29%). Hispanic women (48%) are notable for their criticism of working mothers of young children, easily surpassing white women (35%), black men (26%), black women (31%) and Hispanic men (33%) in their disapproval.

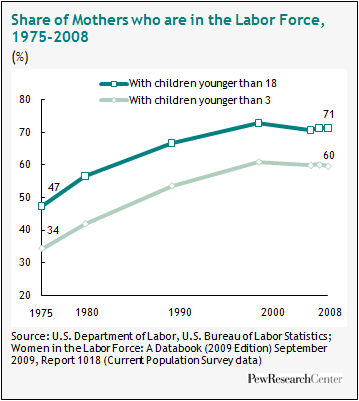

Most mothers are now in the labor force, including mothers of children younger than 3, but that was not always the case. The share of all mothers in the labor force rose to 71% in 2008 from 47% in 1975. Among mothers of children younger than 3, 60% were in the labor force in 2008, compared with 34% in 1975.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Hispanic mothers of young children are less likely than other such mothers to be in the labor force. Among Hispanic mothers of children younger than 3, 47% were in the labor force in 2008. Comparable shares for racial groups are 59% for white mothers and 62% for black mothers.

Other survey data show that over the past several decades, the public has become more inclined to believe that a working mother can do just as good a job with her children as a stay-at-home mother. Answering a General Social Survey question that asked whether a working mother “can establish just as warm and secure a relationship with her children as a mother who does not work,” 60% agreed in 1985. In 2008, 72% of respondents agreed.

Childless Women

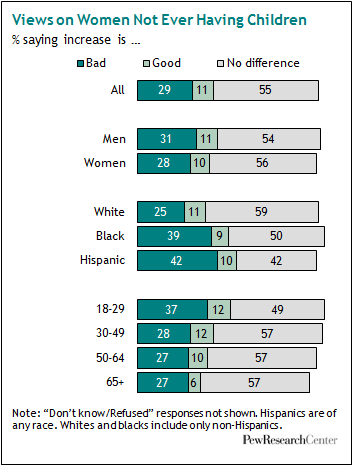

As for rising childlessness, 29% of Americans say this trend is bad for society, 11% say it is good and the majority—55%—say it makes little difference. There is little difference in attitudes by gender, but there’s a distinctive pattern by age. This trend is the only one tested about which the youngest adults are more concerned than older ones: 37% of 18- to 29-year-olds say it is bad for society that more women do not have children, which is nine or 10 percentage points higher than older age groups.

By race and ethnic group, the increase in women without children is of more concern to blacks (39%) and Hispanics (42%) than to whites (25%); whites are more likely to say it does not make much difference.

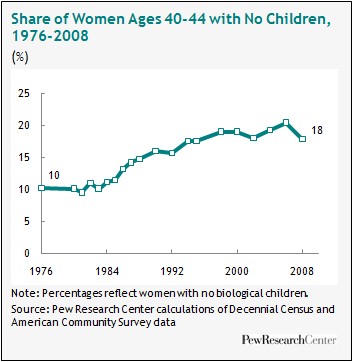

Childlessness has risen rapidly in recent decades. In 1980, 10% of women ages 40 to 44 had no biological children. In 2008, that share had risen to 18%. Childlessness has risen among all racial and ethnic groups, but white women are the most likely not to have had their own biological children.

Aside from the issue of how Americans characterize the impact of growing childlessness on society, data from another survey indicate that they are less willing to criticize people who do not have children. In 1988, 39% disagreed that “people who have never had children lead empty lives,” according to the General Social Survey. In 2002, 59% disagreed.

Racial Intermarriage

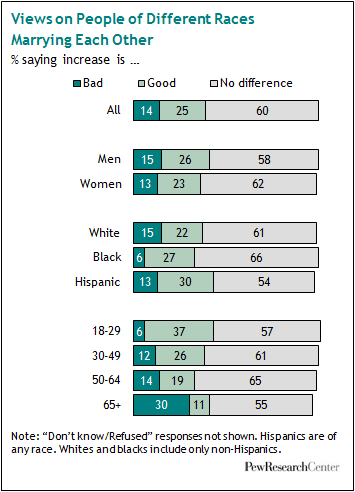

The increase in people of different races marrying each other is deemed good for society by 25% of all adults and bad for society by 14% of adults. Fully 60% say they think it makes no difference. There are some differences by age and race groups. The intermarriage trend is criticized by 30% of Americans ages 65 and older, but the proportion among younger age groups is less than half of that.

Whites (15%) and Hispanics (13%) are more critical than blacks (6%). There is a gap between the most and least educated Americans on this question. Only 8% of college graduates say rising intermarriage is bad for society, compared with 22% of those without a high school diploma.

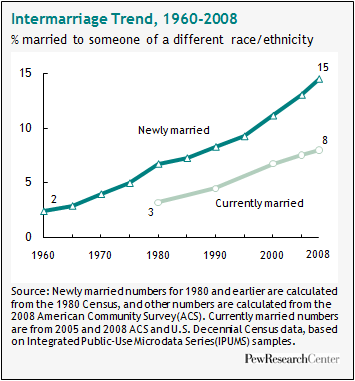

Intermarriage—defined as marriage between either people of different races or between Hispanics and non-Hispanics—has risen in recent decades. In 2008, one-in-twelve married couples included spouses of different races or ethnic groups, according to a recent Pew Research Center report. Among newly married couples, about one-in-seven include spouses of different races or ethnic groups. This proportion has risen sharply since 1960, driven in part by changes in cultural norms, the ending of legal prohibitions against interracial marriage and the large influx of immigrants from Latin America and Asia.

In surveys conducted over the past decade, whites have grown more accepting of interracial marriage within their own families. The proportion of whites who said they “would be fine” with a relative’s marriage to someone who is black, Hispanic or Asian rose to 61% in 2009 from 53% in 2001, according to the Pew Research center’s recent report. However, black approval of interracial marriage declined somewhat. In 2009, 72% of blacks said they would be fine if a family member wanted to marry someone from one of the three other groups. In 2001, 81% said so.

Family Type and Attitudes

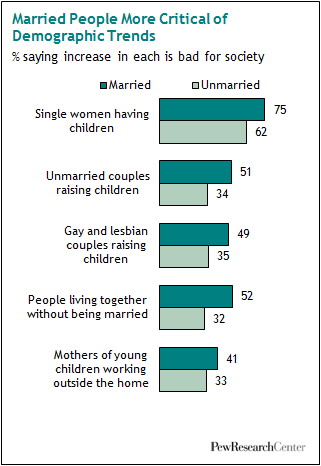

There are notable differences by marital status and family type on questions about whether specific types of new living arrangements are bad for society. Married adults are more critical than unmarried adults of single mothers, unmarried live-in couples with and without children, and same-sex couples raising children. Married parents also are more critical of these arrangements than are unmarried parents.

For example, 75% of married adults are critical of single women who have babies without a man to help raise them, compared with 62% of unmarried adults who say this growing trend is bad for society. About half of married adults say it is bad for society that more people live together without being married (52%), more unmarried couples are raising children (51%) and more same-sex couples are raising children (49%). Only about a third of unmarried adults say these trends are bad for society.

(Unmarried adults include those living with a partner, divorced or separated, single and never-married, and widowed. Widowed adults are more conservative on these questions than the other groups of unmarried adults.)

Married adults (41%) are more critical than unmarried adults (33%) of mothers of young children working outside the home. Parental status makes a difference on this question: Married parents (43%) are more critical of working mothers than are married adults without children (31%) and all unmarried parents (33%), especially single, never-married adults with children (21%).

Party and Religiosity

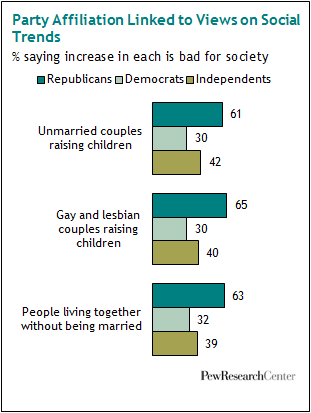

There are notable differences in attitudes toward most of the new living arrangements tested in the survey by political party, ideology and religiosity. Generally, Republicans, political conservatives and adults who attend religious services at least weekly are more critical of these growing trends than are Democrats, moderates and liberals, and less religiously observant adults

On all seven new arrangements tested, Republicans were more critical than Democrats. There are gaps of 30 percentage points or more between the share of Republicans and Democrats critical of the increase in unmarried couples raising children (61% vs. 30%), unmarried couples (63% vs. 32%) and same-sex couples raising children (65% vs. 30%). There also are gaps by ideology, with political conservatives being more critical than moderates or liberals (except for rising childlessness, where conservatives and moderates do not show a statistically significant difference).

The most religious Americans, as defined by attendance at services at least weekly, also are more critical of these non-traditional arrangements (except interracial marriage) than are less religious adults, those who attend services less often. For example, 67% say it is bad for society that more unmarried people are living together, compared with 37% of the moderately religious (those who attend services monthly or less) and 20% of the least religious adults (those who seldom or never attend religious services) who say so.

Links to Other Attitudes

Criticism or acceptance of these new living arrangements is linked to other attitudes about social change. Specifically, adults who are critical of single mothers, same-sex couples raising children and other non-traditional arrangements also are likely to believe that the growing variety of family arrangements is a bad thing, that a child needs both a mother and father at home to be happy, or that marriage is best when spouses have traditional gender roles.

As one example, people who say a child needs both a mother and father at home to be happy are more likely than those who disagree with that statement to say single mothers (83% vs. 45%) or same-sex couples raising children (58% vs. 18%) are bad for society.

Growing Variety of Family Types

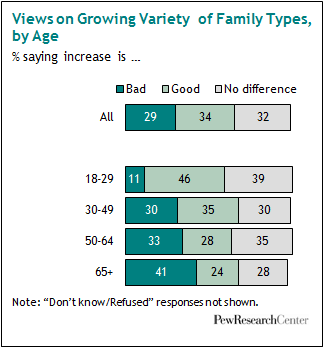

On the question of whether the growing variety of family living arrangements is good or bad, most Americans are neutral or accepting: 34% say it is a good thing, 32% say it makes little difference and 29% say it is a bad thing for society.

Age is an important dividing line on this question. The younger the person, the more likely he or she is to say the growing variety is a good thing—46% of 18- to-29-year-olds do, compared with 24% of those ages 65 and older. Similarly, older Americans are more likely than younger ones to say these new arrangements are a bad thing. Fully 41% of Americans ages 65 and older say these changes are bad, compared with 11% of those ages 18 to 29.

There are no overall gender differences on this question, but there is somewhat of a divide among men and women younger than 50. Women ages 18 to 49 (44%) are more likely than similarly aged men (35%) to say the growing variety of family living arrangements is a good thing. Among the youngest adults, ages 18 to 29, there also is a gender difference: Most women in this age group say the new arrangements are a good thing (55%), while half of men (50%) say it makes no difference. Among men and women ages 50 and older, there is no gender difference.

By race and ethnicity, Hispanics (55%) are more likely than whites (29%) or blacks (37%) to say the new arrangements are a good thing. Both whites (32%) and blacks (24%) are more likely than Hispanics (15%) to say these new arrangements are a bad thing.

Americans with the lowest levels of education and income (who, according to census data, are the least likely to be married) are more likely to approve of the growing variety of family living arrangements. For example, 49% of those without a high school diploma and 39% of those with annual incomes under $30,000 say the growing variety is good.

Marital Status Makes a Difference

Marital status makes a difference in attitudes. Married people (37%) are more likely than the currently unmarried (19%) to disapprove of these new arrangements in the Pew Research Center survey. As might be expected, adults who are living with an unmarried partner (56%) are more inclined than married adults (29%) to see these new arrangements as a good thing. Those who are currently cohabiting (56%) are more likely than people who have lived with an unmarried partner in the past (34%) to say the new arrangements are a good thing.

Parental status also makes a difference in how people respond: 33% of parents, compared with 18% of non-parents, say the new arrangements are a bad thing. (Parents tend to be older, which also plays a role.) Among parents, those who are married are more critical than are those who are single or living with a partner.

Religiosity, conservative ideology and Republican Party affiliation also are linked with higher disapproval ratings for the new types of living arrangements. For example, 45% of very religious Americans (those who attend religious services at least weekly) say these new arrangements are a bad thing, compared with only 15% of the non-religious (defined as those who seldom or never go to religious services). Republicans (48%) are more likely than Democrats (17%) or independents (27%) to consider these new arrangements bad.

Attitudes about the growing variety of Americans’ family living arrangements go hand in hand with other views about social change. People who are optimistic about the future of marriage are more likely than those who are pessimistic or uncertain to say that the variety in living arrangements is good; a 38% share of optimists say so, compared with a 25% share of those pessimistic or uncertain. Those who disagree that a child needs a home with both a mother and father to grow up happily (42%) also are more likely to say the new arrangements are a good thing, compared with those who believe a child needs both parents (30%). Americans who prefer a marriage where husband and wife have traditional gender roles (23%) are less likely to say the new variety is good than are those who prefer a marriage where both spouses have more similar roles (40%). Americans who disapprove of gay and lesbian couples raising children are more likely to be critical of the new arrangements (52%) than are those who approve of those couples (5%).

Attitudes and Definition of Family

People who disapprove of some of the new types of living arrangements also are less willing than those who are approving or neutral to describe unmarried cohabiting couples or parents as a family. As detailed in Section 3, nearly all adults say that they consider a married couple with children to be a family. Nearly nine-in-ten describe a married couple without children or a single parent with children as a family. Eight-in-ten say that an unmarried couple with children is a family. However, only 63% say a same-sex couple with children is a family; 45% say a same-sex couple without children is a family; and 43% say a live-in unmarried couple without children is a family.

On the question of whether a single parent with children fits the definition of family, most adults say yes, no matter whether they approve or disapprove of new living arrangements in general. However, there are gaps in the willingness to define a single parent as a family between those who agree that a child needs a mother and father to be happy (81% of whom say a single parent with children is a family) and those who disagree (93% of whom say a single parent with children is a family). There also are gaps on this question between those who approve and disapprove of same-sex parents.

Similar patterns prevail when respondents are asked whether unmarried couples with children constitute a family. Most adults say yes, but there is an approval gap linked to attitudes about same-sex parents, views about changing family arrangements, those who say a child needs a mother and father in order to be happy, and those who have differing opinions about gender roles in marriage.

When it comes to same-sex couples with children, less than half of adults who say new types of living arrangements are generally a bad thing (33%) say this type of household is a family, compared with much higher shares among those who endorse the new arrangements (80%) or say they make no difference (75%). As might be expected, only 30% of those who say same-sex parents are bad for society agree that same-sex couples with children are a family, compared with about nine-in-ten adults among those who endorse (92%) the rising number of same-sex parents or don’t think it makes much difference (89%). Half of those who say a child needs a mother and father to be happy (50%) say same-sex couples with children are a family, compared with 89% of those who disagree that a child needs a mother and a father to be happy.

Supporters of traditional gender roles in marriage (45%) are less likely to consider same-sex couples with children to be a family than are supporters of similar gender roles (71%).

Cohabiting Adults

This section explores the experiences and attitudes of adults who say they have ever lived with an unmarried partner.

Cohabitation in the U.S. has become so established that most couples who marry these days live together first.30 But as an arrangement, it is quite varied, including couples who live together for differing amounts of time and who may or may not have children.

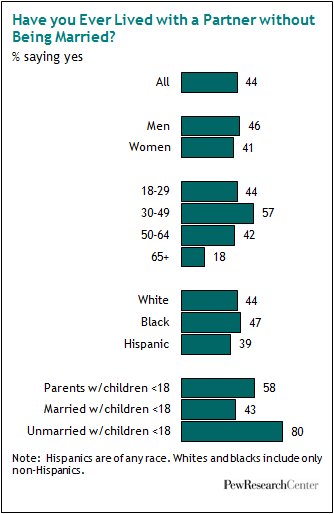

Among survey respondents, 44% say they have lived with a partner without being married: 36% of whom cohabited in the past and 8% who say they are doing so now.31

The age group most likely to have lived with an unmarried partner is 30- to-49-year-olds, more than half of whom (57%) say they have done so. Only 18% of adults ages 65 and older say they have lived with an unmarried partner. By gender, men (46%) are somewhat more likely than women (41%) to say they have cohabited.

Some 47% of blacks say they have cohabited, compared with 44% of whites and 39% of Hispanics. Among black men, 58% have cohabited, compared with 38% of black women. There are no differences between people of different levels of education or income on the question of whether they ever have cohabited, but the lowest income adults are more likely than the highest income adults to be currently in an unmarried partnership. Younger parents—those with children younger than 18—are more likely to have cohabited (58%) than those whose children are all ages 18 and older (30%).

Most married parents of children under 18 say they have never cohabited (57%), but most unmarried parents of children under 18 say they have (80%). According to a recent estimate by researchers based on data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 40% of children spend some time in a cohabiting family by age 12.32

Those with conservative ideology (35%) are less likely to have cohabited than are moderates (46%) or liberals (55%). By religiosity, the most religious (27% of adults who attend services at least weekly) are least likely to have cohabited, compared with the moderately religious (45% of those who attend services monthly or less) and those who are not religious (63% of those who seldom or never go to services).

Step toward Marriage?

Among Americans who have ever lived with an unmarried partner, nearly two-thirds (64%) say they thought about it as a step toward marriage. That includes 53% of those now living with a partner, compared with 67% of those who cohabited in the past. There are no significant differences by age, race or gender on this question, among people who ever lived with a partner.

Adults with annual incomes of $75,000 or more (69%) are more likely than those with annual incomes under $30,000 (59%) to say they saw cohabitation as a step toward marriage. And, as might be expected, a higher share of married former cohabiters (74%) say they viewed living together as a step toward marriage, compared with currently unmarried people who have ever cohabited (56%).

Some 70% of self-described conservatives say they thought about cohabiting as a step toward marriage, compared with 59% of liberals and 66% of moderates. The least religious Americans (defined as seldom or never going to services) also are least likely to have thought of cohabiting as a step toward marriage—53%—compared with 72% of the moderately religious (attending services monthly) and 74% of the very religious (attending services at least weekly).

Looking at actual experience, about nine-in-ten married people who have cohabited say they lived with their current spouse before they got married—59% only with their current spouse and 30% with their current spouse and with someone else. Married adults with annual incomes of $75,000 or more who cohabited in the past are notably more likely to have lived only with their current spouse before they got married (67%) than are married people with annual incomes under $30,000 (43%). Lower income adults are (48%) are more likely than the higher income adults to have lived both with their spouse and someone else (26%).

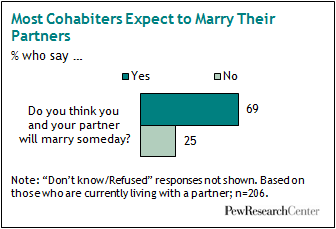

As for the marital intentions of people who currently are cohabiting, 69% say they expect they will someday marry that person, 25% say they don’t expect to and 6% don’t know or would not answer.

Economic Considerations

About a third of adults (32%) who ever have lived with an unmarried partner say finances were an important consideration in their decision to move in together. Blacks (44%) are more likely than whites (30%) to say so. So are 30- to-49-year-olds (38%), compared with 50- to 64-year-olds (25%).

The Census Bureau recently released a report noting that the number of male-female cohabiting couples increased to 7.5 million this year from 6.7 million in 2009. Analyzing the characteristics of cohabiting couples, the report found, among other things, that a higher share of men did not work in newly formed 2010 couples, compared with newly formed 2009 couples.

The report said, “Taken together, the ways in which newly formed couples in 2010 differed from existing couples suggest that economic situations such as longer-term unemployment may have contributed to the increase in opposite-sex cohabiting couples between 2009 and 2010.”33